This Week in Native American News (5/11/18): Putting Community First, Finding Pele, and Alaska Natives on PBS kids

May 11, 2018

Great People Doing Great Things: Doctorate Cohorts Put Community First

Ephriam Alexander came to the Carlisle Indian School from the village of Kanulik on the Nushagak River and Bristol Bay in southwestern Alaska, but died in Lititz, Pa., near Cocalico Creek, shown here. He’s buried in the Lititz Moravian Congregation Cemetery. Historical photo courtesy of Cumberland County Historical Society.

Most people go to college to enhance their education, bolster their professional status and increase their earning power. But a doctoral cohort from New Mexico got their degrees to enrich their communities and build up their nation.

Meet the Arizona State University Pueblo Indian doctoral program Class of 2018.

“When our tribal leaders came to our orientation to give their blessing and a word of encouragement, they told us that we were about to embark on a spiritual journey,” said Doreen Bird, who received a doctorate from ASU’s School of Transformation this week after three years of hard work, research and sacrifice. “We realized at that point it wasn’t about us anymore. It’s about our communities.”

Read the Full Story Here

Other People You Should Know...

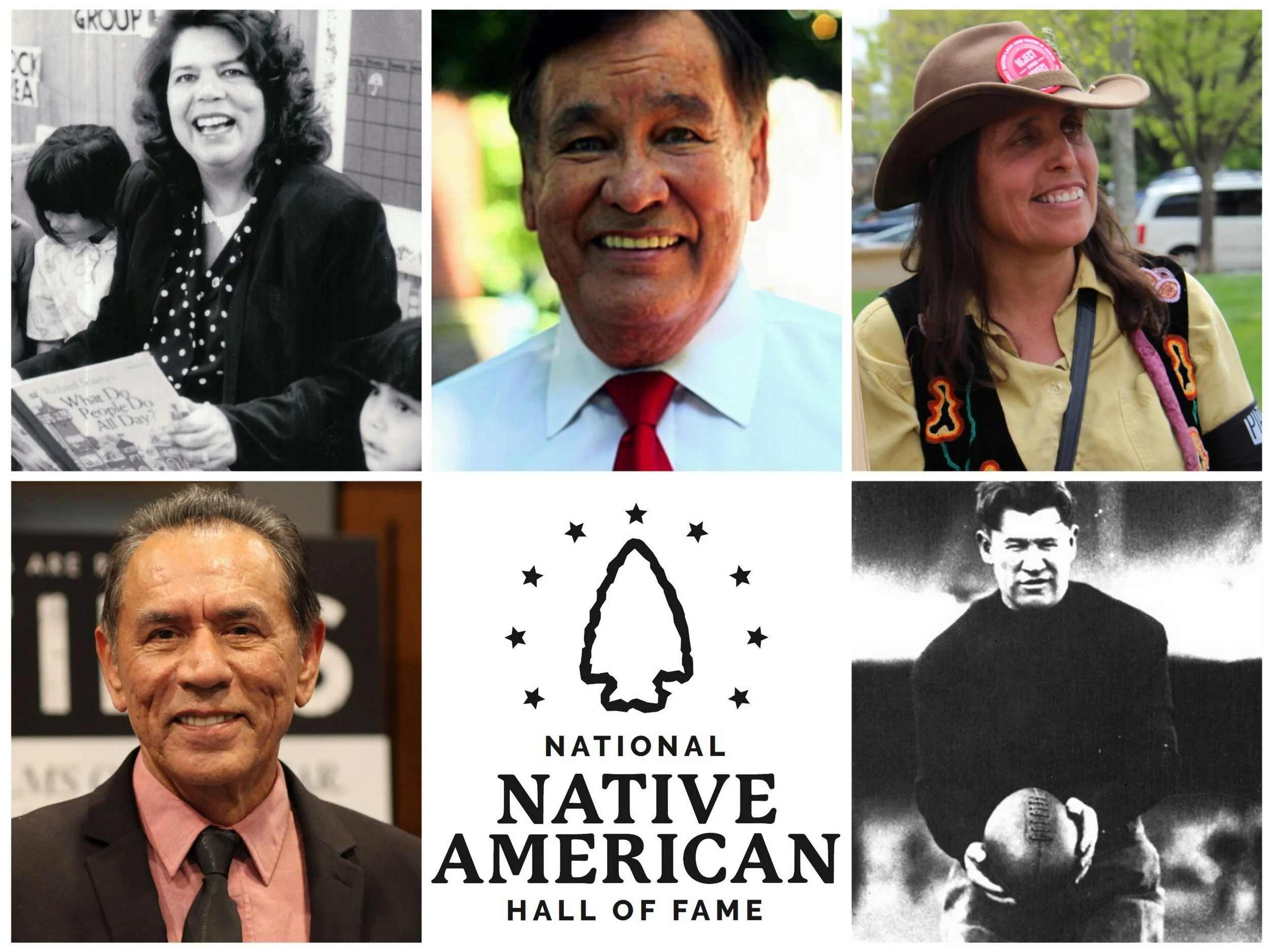

National Native American Hall of Fame Inaugural Induction Ceremony at Phoenix Indian School Memorial Hall-List of Potential Inductees Released

Ten years ago, James Parker Shield, Little Shell Chippewa and Cree, started thinking about a potential organization that could recognize Native Americans after visiting a Cowboy Hall of Fame and a Country Music Hall of Fame. Realizing there wasn’t such a place, he decided to come out of retirement to establish the National Native American Hall of Fame.“I just felt that so many Natives that had done so much for Indian Country were being overlooked and possibly forgotten,” Shield told Indian Country Today.

Native Hawaiians consider volcanic eruptions a 'rebirth'

The lava lake at the summit of the Kilauea volcano near Pahoa, Hawaii. Photo: ABC NEWS

The recent volcanic eruptions from Mount Kilauea in Hawai'i are a sign of spiritual reconnection to traditional deities for the native people of the Big Island. The volcanic activity has destroyed 26 homes to date around the Kilauea area, but the cause behind the loss is also a significant moment for native Hawaiians both spiritually, and metaphorically.

Traditional Hula expert Mehanaokala Hind told Kawekōrero, "For the hula practitioners, this has been incredibly significant, our spiritual reconnection with our deities and also illustrating that for the rest of the people that live here in Hawai'i."

"On one level it's a cleansing of our 'aina (homes) and a rebirthing of our 'aina, on another level, it's a reminder again that we must pay attention to all of the natural phenomena that are going around us and so those are really strong signs that are coming," says Hind.

Read the Full Story Here

You Might Also Be Interested in...

Pele: Who is Hawaii's volcanic fire goddess?

According to Lilikala Kame'eleihiwa, a professor at the Kamakakūokalani Center for Hawaiian Studies, Pele is regarded by Hawaiian traditionalists as a divine akua, or a sacred spirit of an earthly element. Kame'eleihiwa, whose family's personal akua is Pele, said there are over 400,000 element gods in Hawaiian tradition.

Legend has it that Pele was born in Tahiti, but after angering her sister Na-maka-o-kaha'i, the akua of the sea, Pele was banished from the island. The akua embarked on a journey in exile in pursuit of a fiery dwelling.

Hawaii residents leave offerings for volcano goddess Pele as lava destroys homes

As molten lava continues its relentless, unstoppable flow down the Kilauea volcano, many on Hawaii's Big Island are looking to the ancient volcano goddess Pele for protection.

"Many native Hawaiians believe that lava is the kinolau, or physical embodiment, of volcano goddess Pele. Poking lava with sticks and other objects is disrespectful," according to the National Park Service.

Pele is known to be unpredictable, so Hawaiians have traditionally left gifts and offerings to keep her happy. That tradition continues today, and some residents have left leaves in front of their homes and flowers in cracks caused by the volcano for good luck.

The Tourists are Coming... Are you one of them? Read on.

Grizzly's Gifts offers lots of different kinds of souvenirs, from funny t-shirts to some native american replicas. Photo: Grizzly's

Tourist season is almost among us. We begin to prepare for the arrival of the ships and the influx of visitors. You can see the stores downtown, that only open during tourist season, begin to take the coverings off the windows. Some local shops offer huge sales before the season begins to make room for new inventory with many of those items representing Alaska.

As an Alaskan Native, I always take time to spot the insane amount of “Alaska Native” items being sold. I think of all the absolutely amazing Native artists who have a hard time getting their art into local tourist shops. Then I think of all the “Alaska Native” art made in Indonesia and China. Put a face in a parka and put it on something that says Alaska. Take a caricature that resembles a totem pole and put it on something that says Alaska. These items are obviously not good representations of Alaska, but the shop owners feel they sell.

One of the most common things we hear as Alaskan Native artists from a shop owner is, “Your art is too expensive.” Which to us sounds like “We don’t want to pay you for your time, labor and cultural expertise so instead we are going to sell the idea of your culture with this mass-produced item made in Indonesia instead.” Sometimes the shop owner tells us “it’s not traditional enough” while standing next to their totem pole bottle openers. Sometimes the shop owner tells us “We don’t sell Alaskan Native art, only Alaskan things.”

Read the full story here

Tomahawk Chops and Native American Mascots: In Europe, Teams Don’t See a Problem

Buffalo Ben, the official team mascot for the Belgian soccer team K.A.A. Gent. His sidekick is a female version named Buffalo Mel.CreditJimmy Bolcina/Photonews, via Getty Images

Benjamin Bundervoet was wearing his normal workday outfit — a blue-and-white feathered headdress, a fringed tunic and chaps, bright paint streaked across his cheeks — as he stepped onto the grass.

For the next few hours, Bundervoet would be Buffalo Ben, the official team mascot for K.A.A. Gent, a top Belgian soccer team. As the players warmed up before kickoff at a recent home match, Bundervoet smiled and waved a flag bearing the team’s logo, the profile of a Native American, which is also plastered around the Ghelamco Arena.

Scenes like this play out every weekend across Europe, where teams big and small and across a variety of sports employ Native American names, symbols and concepts of wildly variable authenticity in their branding. There’s the hockey team in the Czech Republic that performs a yearly sage-burning ritual on the ice, the rugby team in England whose fans wear headdresses and face paint, the German football team called the Redskins and many more.

For years, these teams were insulated from the vigorous discussion about the use of this type of imagery by sports teams in the United States, where critics long ago deemed the practice offensive and anachronistic. This year, the Cleveland Indians announced that they would stop using their Chief Wahoo logo on their uniforms beginning in 2019, continuing a decades-long trend in which thousands of such references have disappeared from the American sports landscape.

But these ideas are slowly being challenged, and increasingly these teams are finding themselves being asked to confront the same questions of representation, appropriation and stereotyping. K.A.A. Gent, for example, devotes a lengthy page on its website to the history of its logo and nickname, but notes only that the club is “aware of the public debate in American society around the use of stereotypical images and caricatures.”

Read the Full Story Here

It's hard to fit so much news in such a small space.

To read all of this week's news, visit the LIM Magazine.

Sign up to get these emails in your inbox and never miss a week again!